Introduction

Satire: the art which

“afflicts the comfortable

and comforts the afflicted.”

H. L. Mencken (1880-1956)

(Roukes, 1997, p. 85)

The principal objective of my thesis is to explore the value of satirical art and

caricature through a studio-based research project. Another purpose is to confirm the

notion that satirical art and caricature can foster visual literacy through the imagery of

creative metaphor. I am also looking forward to confirming the importance of introducing

satirical creativity into Art Education curricula as an essential element of artistic and

cognitive development.

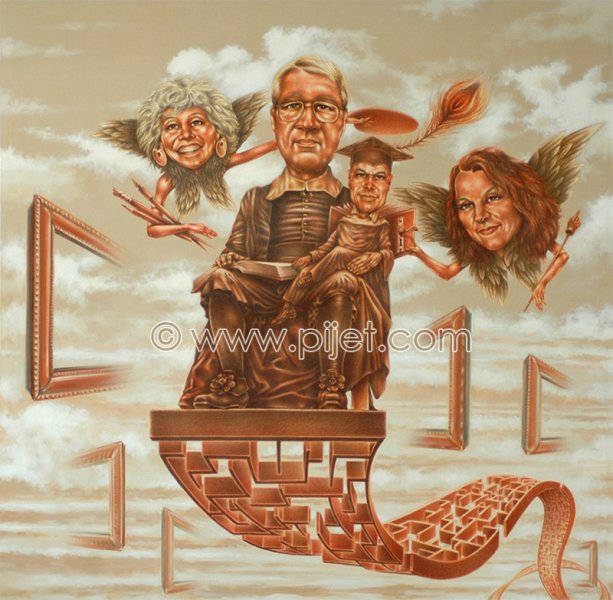

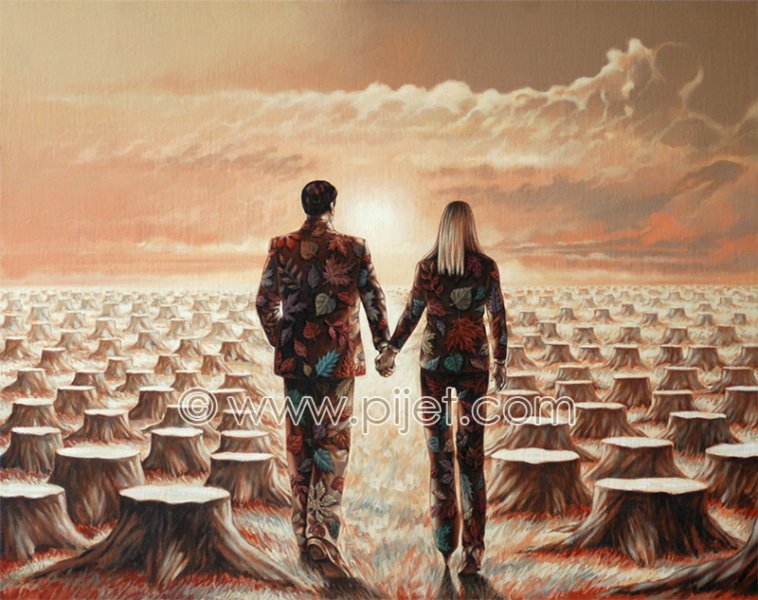

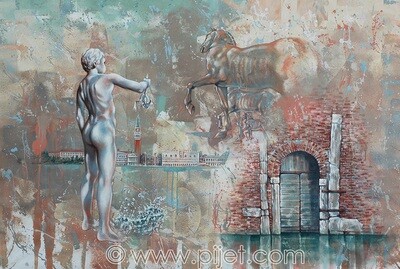

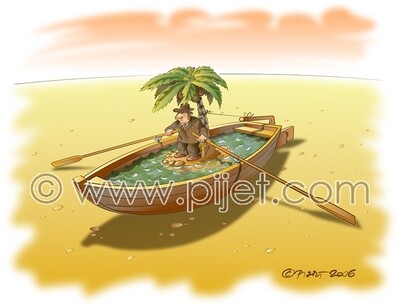

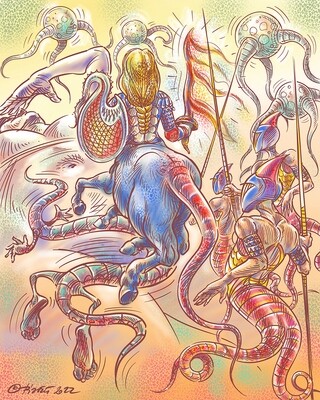

I did six satirical paintings specifically for the purpose of this thesis. The completed

artworks were shown to a group of sixteen voluntary participants. The participants were

asked to answer a set of questions regarding the content of the artworks. These questions

explored the educational possibilities of satirical art and caricature. The series of images

was created to investigate how effectively satirical art contributes to knowledge and

visual literacy.

The satirical imagery presented uses information embedded in metaphoric

symbolism. I hoped that this would provoke the viewer to active, deductive reflections in

deciphering my paintings. The language of humorous imagery evokes various states of

mind and, as such, shape one’s critical and aesthetic sensibility.

The recorded audience responses to the questions about the metaphoric satirical

narrative conveyed in my paintings formed the data for my study. Through my research I

confirm the educational importance of satirical art and caricature.

I believe that the art of caricature and satirical expression have a significant

advantage over other artistic forms of visualization because these forms generate

knowledge as a kind of social pedagogy. This is the main reason why satirical imagery

should be studied in art classes.

CHAPTER 1

Defining the Subject

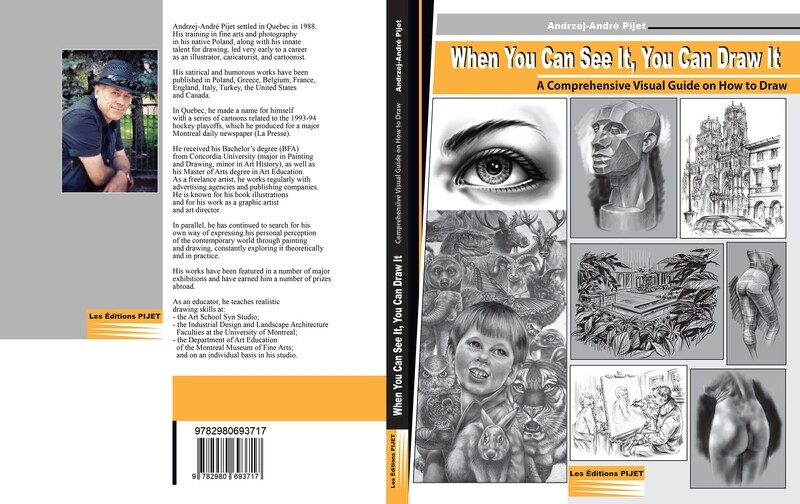

The theme for this thesis originated from my professional experience as an artist

and educator. It appeared to me that the satirical image is rarely understood the way an

artist intends it to be. The main reason for this is due to the fact that “…we can only

recognize what we know” (Gombrich, 1982, p. 151).

The question I pose, and to which I intend to respond, is based on my many years

of experience as a practicing artist and caricaturist. My satirical artworks have been

published in many different newspapers, journals, magazines, books, catalogues and

advertising publications in different countries. I have participated in many life-drawing

events in Canada and various festivals around the world for caricature. The experiences I

have collected over the years I would like to share with my students by teaching

caricature and the skills of satirical expression. This would benefit students who are

interested in the art of satirical drawing and caricature as an educational tool.

Since my early childhood in Poland I have been surrounded by satirical art,

caricatures, and all kinds of visual libraries due in part to a massive collection of various

magazines, albums, catalogues, and books, which were stored in my uncle’s studio and

served him as references for his paintings. I was lucky enough to have easy access to

such a great “encyclopedia” of satirical art. The satirical imagery from my uncle’s

collection stimulated my desire to learn more about the world I was experiencing. This

constant exposure to visual material created in my mind a desire to become an artist able,

as my uncle was, to express his feelings and observations through the visual language of

satire and humor. Furthermore, through my professional activities such as caricature

animations, participation in international festivals of caricature and press drawing, I have

witnessed the happiness and enjoyment expressed by the many people who participated

in these events with great excitement. It is why I think that satirical art can play an

important role in education curricula by teaching students to create an intellectually

resourceful and challenging art that explores critical thinking and humoristic opinions on

important issues in our contemporary society. My professional experience taught me that

on many occasions satirical art is misunderstood because the viewer lacks knowledge

about the represented subject. In spite of these experiences, I believe that the art of

caricature can teach visual literacy like no other form of art.

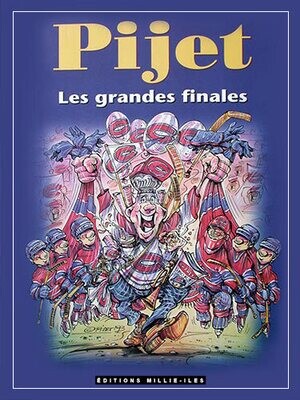

It needs to be explained here that I am discussing satirical art and caricature

according to high artistic standards, that narrative is formed through metaphorical

imagery and without the presence of captions, which could play the role of a leading

(meta) narrative. In my opinion, the artworks of Mark Tansey could serve here as a

perfect example of such elaborate artistic quality. As a consequence, my concept of

caricature and satirical art excludes any form of drawing and painting where the editorial

role is to serve as an illustration of the published text rather than standing on its own.

“Rockwell’s son Peter says that his father ‘believed that the picture and the observer

should encounter each other directly without interference from words or interpretation’”

(Barrett, 2003, p. 70). The combination of text and drawing significantly degrades the

artist’s visual story, exposes the limits of his creativity and attaches a label of

commerciality to his work. An image, whose only purpose is to illustrate the text, belongs

to a different category of humoristic expression, namely illustrated comics and cartooning

gags, where all is explained and the analytical faculty of the viewer is in consequence

limited or non-existent. In such cases the narrative of the image is imposed on the viewer

rather than proposed to him/her for cognitive deduction and visual contemplation. It is

why most of the important international competitions of caricature and satirical art do not

accept drawings with captions from participants. It is an unfortunate fact that, in general,

the understanding of the art of caricature and satirical drawings and all these important

nuances are ignored, and that all forms of satirical creativity are collected under one

umbrella of caricature and cartooning. So far, to my knowledge, no-one has tried to

distinguish between these various forms of satirical art in order to bring about respect for

and recognition of this form of artistic creativity and eradicate the generalized stigma of

commerciality and lowbrow art that is attached to this form of art by the “fine art” world.

This distinction is important for different categories to be established.

The word ‘caricature’ has a generalized meaning and presents a kind of distortion

of reality, not only portraiture, but also other realities represented metaphorically in a

satirical way. From the academic point of view, we can say that caricature is a diagram of

the satirical thought represented in visual figurative data. The caricaturist creates his/her

artwork by the same process of cognitive reflection and aesthetic sensation as any other

artist does. The only difference is that he/she possesses a deeper deductive voice and

sense of elaborate observation enabling the viewer to see how much of the surrounding

reality is changed.

The criteria for the art of caricature and satire, which I have already described in

the text above, belong to the category of fine arts as a form of artistic expression; “Pablo

Picasso elevated caricature to the status of fine art” (Roukes, 1997, p.59). Through the

history of Western Art, many artists “…used caricature as a style of painting and drawing

ranged from post-Impressionists to German Expressionists, to Modernists. Toulouse-

Lautrec, Max Beckmann, Edward Munch, James Ensor, Otto Dix, Paul Klee, and Pablo

Picasso are notables” (Roukes, 1997, p. 90).

Roukes (1997) states the following:

Examples of satirical humor can be found in all major movements in

American art–Pop Art, conceptual art, political art of the 1960s and 1970s,

earth art, graffito, performance art, video art, installations, and so forth. Satire

has invaded domains of both classical and contemporary art and has

unabashedly mixed the sacred with the profane. (p.92)

The contemporary artists who correspond more closely to my perception and

aesthetics of satirical art are Erró, Mark Tansey, John Curin and Neo Rauch. These

artists, among many others, reflect satirically on various aspects of contemporary reality

in their own way and time. When looking further into the history of satirical painting and

caricature, artists like Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Giusseppe

Arcimboldo and Annibale Carraci were the earliest precursors of this form of artistic

expression in drawing and painting. The list of artists who have followed the satirical

path is very long, and each century has had at least a few.

In regard to the subject of my research, it is necessary to describe in a few words

what it means to be satirical, and what visual literacy is. The description of satire

according to various sources and publications differs slightly, but the one I find most

useful is given by Cuddon (1999) in his dictionary.

Cuddon (1999) states the following:

The satirist is thus a kind of self-appointed guardian of standards, ideals and

truth; of moral as well as aesthetic values. He is a man …who takes it upon

himself to correct, censure and ridicule the follies and vices of society and

thus to bring contempt and derision upon aberrations from a desirable and

civilized norm Thus satire is a kind of protest, a sublimation and refinement

of anger and indignation. As Ian Jack has put it very adroitly: ‘Satire is born

of the instinct to protest; it is protest become art.’ (p. 780)

The Encyclopedia Britannica on line describes satire as “artistic form… in which

human or individual vices, follies, abuses, or shortcomings are held up to censure by

means of ridicule, derision, burlesque, irony, parody, caricature, or other methods,

sometimes with an intent to inspire social reform.” “The satire is a verbal caricature

which distorts characteristic futures of an individual or society by exaggeration and

simplification” (Koestler, 1964, p. 72).

Koestler (1964) also states the following:

The comic effect of the satire is derived from the simultaneous presence, in

the reader’s mind, of the social reality with which he is familiar, and of its

reflection in the distorting mirror of the satirist. It focuses attention on abuses

and deformities in society of which, blunted by habit, we are no longer aware;

it makes us suddenly discover the absurdity of the familiar and the familiarity

of the absurd. (p. 72-73)

It is essential to acknowledge here that the meanings of the word ‘satire’ are vast

and can be understood in many ways.

By visual literacy, I mean the viewer’s ability to work with the various elements

that combined create a visual narrative in the composition of an artwork, and the ability

to connect the meaning of the work with its appearance. It is about the cognitive

perception of symbolic and metaphoric signs and forms encapsulated in the painting’s

composition, photographic imagery, sculpture and other acts of artistic expression. The

above description corresponds to the general definition of visual literacy, which one can

find in dictionaries and other published sources.

For example, Eisner (2002) states the following:

By promoting visual culture I refer to efforts to help students learn how to

decode the values and ideas that are embedded in what might be called

popular culture as well as what is called the fine arts […] any art form can be

regarded as a kind of text, and texts need to be both read and interpreted, for

the messages they send are often ‘below the surface’ or ‘between the lines’

(p. 28).

Visual literacy is “understanding how people perceive objects, interpret what they

see, and what they learn from them” (Elkins, 2009, p. 2). Christopher Crouch describes

visual literacy as “…knowing how to use and access information to understanding

information’s social, cultural, and philosophical contexts” and it is “…an active

process…” which “…involves a critically analytical reading of visual text” (Elkins, 2009,

p. 195). In addition “…visual literacy is not a solitary, individual act, but part of a wider

set of social practices.” So, “To find meaning is to negotiate with the visual text, to

engage with it on any number of levels, and to be involved in discovering how that act of

negotiation itself is constructed” (Elkins, 2009, p. 196).

The entire version of this thesis is available for downloading on the Concordia University Research Repository (PDF).