Delacroix’s Painting Liberty Leading the People Analyzed Through the Various Art Historical Methods.

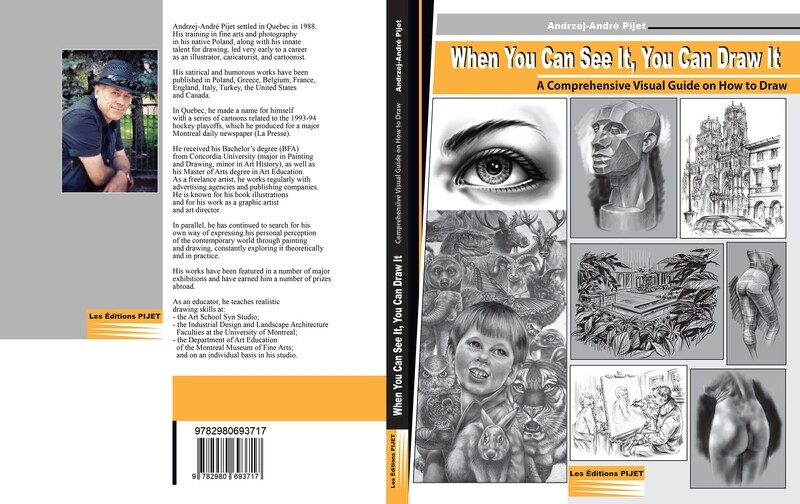

Through the history of humanity the visual representation of the “Liberty” concept has been practiced in many cultures and depicted in many different ways. The pictorial image of “Liberty” and its meaning varied from one country to another and was mostly represented as a female character and as a symbolic personification of national independence.[1] Woman’s image was used to represent divine purity, especially in religious, legendary or mythical creations. In the Patriarchal systems of various societies the feminine image was used as a symbol to represent the best of what humanity had to offer. At the same time socially women were treated as the submissive objects of the men’s desires with very limited personal liberty and respect. Eugene Delacroix for his vision of “Liberty” appropriated the feminine image to connect together the two worlds: a mythical world and a popular realistic world. Delacroix’s references symbolize the antique divinities. They were motivated by his romantic spirit and certainly not by the modern concept of the “Gaze” (Wiseman, 1998). With time his image was adopted as a brilliant allegory of freedom to many. The popularity of the painting Liberty Leading the People (see fig.1) largely exceeds French borders. The artwork was and still is appropriated by many to various utilitarian and promotional aspects of contemporary realities (see fig. 4, 5, 6). Its intriguing particularity is still controversial and subjected to scholarly[2] critiques.

The critical theories of art appeared as comprehensive system of understanding the arts’ structural complexities in the second part of the nineteenth century and evolved in many various conceptual approaches in the twentieth century.[3] These theories are constantly evolving as important academic tools in the effort to dissect and understand various aspects of artistic creation. The application of these various methods in studies of an artwork’s intellectual content can be conducted through different scholarly approaches. Reviewing some of these methods in practice it is interesting to see how certain aspects of Delacroix’s painting Liberty Leading the People could be read, especially when approaching the subject of feminine representation in Delacroix’s socio-political masterpiece. For the purpose of this enquiry, three different methods will be adopted; the first is Erwin Panofsky’s Iconographical analysis and Iconic interpretation; the second is Heinrich Wolfflin’s Formalist approach; and the third is Arnold Hauser’s[4] Social History of Art.

Panofsky developed his method studying the Renaissance paintings, but his way of apprehending the essence of an artwork can apply to the most objects of art. Panofsky divided his system into three basic elements: Pre-iconographical description, Iconographical analysis, and Iconological interpretation, called also the intrinsic meaning. Each element functions separately and completes another. The summary of all three projects is the final comprehensive conclusion about the artwork in question.

Following Panofsky’s system of pre-iconographical description, viewing Delacroix’s painting, Liberty Leading the People, one sees a quite large canvas (see fig.7) where a group of armed individuals is moving spontaneously. They are following a female figure that is exposing a large part of her bare breast. Her imposing features diminish the importance of the two life-size, juxtaposed, dead figures on the first plane in the lower part of the painting. The woman is carrying in her right hand a three-colored flag, and in the other hand she is holding a rifle armed with a bayonet. To her right, a young boy waving his hands equipped with guns is accompanying the female character in her marching on the barricade. Behind the woman, to her left a group of armed men with rifles, pistols, and sabers is following her to attack the enemies situated somewhere outside the frame, perhaps in front of them. In the center of the painting, just in front of the female character, another person is placed in horizontal position obstructing the progressive movement of the group of armed men. It seems as if the individual is trying to rise up and follow the woman, encouraged by her vitality. In the background behind the front characters the signs of battle are visible at the right corner of the artwork. The silhouettes of buildings and some people are emerging from a fuzzy and smoky landscape indicating some signs of street fighting. In general, the image clearly gives the impression of an armed conflict. The spontaneity of the movement, initiated by the vitality of the central female character, reveals certain influences from the Baroque, especially the spontaneity of Rubens’s[5] euphoric movement and color. Through the collection of all mentioned visual elements of the artwork it is possible to apprehend the particular moment of the French history to which the image is referring. The style of clothing is typical to the first part of nineteenth century period, as well as the two different models of the rifles[6] and the pistols carried by the depicted characters on the painting. The recognizable shape of the Notre Dame church towers visible on the right side of the painting’s background helps to localize where the action takes place. In this case it is in Paris. The optimal historic reading of the image would be related to the socio-political struggles that were taking place in France from the end of eighteenth century until almost the end of nineteenth century. In our case it would be the representation of the “July Revolution”[7] in the year 1830, which was limited only to the Parisian district. The artwork size[8] corresponds with the dimensions reserved usually to the heroic historical paintings and it is typical for the Romanticism.[9] The bare breasted female character irrationalizes the historic reality and suggests its allegoric presence.

The completion of the first general description of the reviewed artwork, permits me to begin the iconographical analysis. The pyramidal composition of the painting directs the viewer to the top of the canvas, where the female bare breast shocks in its obvious appearance and gives an impression of illogical exposure unless we take in consideration the woman’s sculptural posture. Delacroix, for his representation of Liberty, appropriated the position of the sculpture Nike of Samothrace[10] replacing the wings with the hands holding the national flag of France and the rifle as a symbol of protection of the national freedom. The Phrygian cap on the woman’s head is a symbolic reference to the emblem of the first French revolution.[11] The bayonet on the rifle refers to the spear kept originally by Marianne[12] in her hand. The woman’s bare foot standing on the solid ground emphasizes the allegoric and the sculptural representation of the Greek goddess, “Victory.” Besides the allegorical references, Delacroix gave also the “Liberty” the appearance of the woman of the people. According to the historic sources, Delacroix was inspired by the real story of a woman who took the place of her killed brother on the barricade and fought bravely killing many royal soldiers before she was killed too.[13] Delacroix’s “Liberty” represents the artist’s homage to many women fighting besides the men during the July revolt.[14] “Liberty’s” dress refers to the “Peplos,” which Greek women wear and its yellow[15] color symbolizes the power of divine energy, light, stability, sublime purity of judgment, spiritual maturity, and prosperity. On the “Liberty’s” left side the young boy[16] with the waving pistols, symbolizes the new generation, which is revolting against the ruling authorities and hungry for social change. The marching boy is partly shadowed by the “Liberty’s” elevated posture, which suggests that he is under her protective influence. On her right side Delacroix painted a symbolic representation of French society. The group represents different social classes united together in order to defend the revolutionary principals of liberty, fraternity, and brotherhood. “Liberty” is staring at the man[17] in front wearing clothes typical of the period, with a top hat on his head and the rifle in his hands. He is a symbolic representation of either the progressive French nobility or revolutionary middle class. “Liberty’s” direct look at the leading character indicates that she is putting him in charge of the fight for the better tomorrow of the French nation. The crawling character of unspecified gender[18] at the center of the artwork represents the French Republic trying to rise again, encouraged by the brave spontaneity of the marching goddess. The red, white, and blue colors joined together at her waist suggest the colors of the French flag carried in “Liberty’s” hand. The figure is connected with the half-naked, dead body of the man wearing white shirt as a symbolic interpretation of the sacrifices the nation has to make in order to protect her liberty and social equality. The dead soldiers laying on the right side of the painting refer to the royal forces. One body is a Swiss grenadier of the Royal Guard and another is a cuirassier. Both bodies symbolize the falling despotic monarchy of King Charles X.[19]

The final stage of Panofsky’s method permits the iconological synthesis of Delacroix’s painting. Taking into consideration already known elements from the previously conducted analyses it is evident that Delacroix emphasizes the female aspect in his artwork. For Delacroix, the image of woman symbolizes all the positive aspects of humanity. He depicts an image of the bare breasted woman in order to make a sublime symbolic reference to protective motherhood in its entire complexity. Her uncovered breast does not have sexual connotations. He desired to reflect the troubled realities of the civil disorder through the allegoric veil of his creative sensibility. The artist’s socio-political consciousness did not permit him to be indifferent to the events of his time. Furthermore, in order to be considered for the future contracts[20] he had to take a political stand in these significant struggles for the new social order. Delacroix as a Romantic painter was preoccupied by the realities of his epoch. Delacroix’s fragile character forced him to participate in the revolution with his talent and not with a weapon. The painting depicts the visualized synthesis of the social changes Delacroix was witnessing and was overwhelmed by the July events.[21] The painting is executed in the same heroic spirit and great colorist treatment as in his previous artworks.[22]

In reference to Delacroix’s treatment of color it is appropriate to explore Liberty Leading the People in the context of formal analysis as suggested by Heinrich Wolfflin. He developed his theory comparing the art of two periods respectively: Renaissance and Baroque. The theory consists of several principal analytic approaches: the development from linear to painterly, from plane to recession, from closed to open form, from multiplicity to unity, and the subject absolute and relative clarity. In Delacroix’s painting a symphony of colors are arranged in the accordance to the musical score. The ambiance of the dramatic space is moving successively to the top of the painting’s pyramidal structure. The unity of various tonalities of the dark colors is broken at the top of the painting, where the red, white, and the blue prevail. The right part of the artwork slightly to the middle erupts with light yellow surface attracting the attention to the energetic chromatic movement of the unlighted silhouette of the woman representing allegorically the “Liberty.” In the context of perspective the silhouettes at the front have various vanishing points in comparison to the background. The compositional structure of the artwork suggests to the viewer to accept the presence of the vanishing point, as strongest on the left side of the painting. It exceeds the borders of the frame. The chromatic rendition at the top section of the artwork emphasizes the psychological drama of the depicted situation. When the artwork is examined from the viewer’s point of view, the life size silhouettes in front and the compositional framing encourage an emotional identification with the historic event. A close investigation of the painting surface reveals Delacroix’s brash strokes indicating the spontaneous application of the oil medium on the canvas. Looking closely at the artwork it becomes evident that the artist’s main concern was to give an impression of reality to this allegorical situation. Delacroix definitely had a painterly approach and not a linear one. Delacroix argued[23] that the linear approach restrains the object’s visual flexibility and does not serve his purposes to express the molecular movements of the various segments in his compositions. The linearity of the elements of his painting is partial and discontinuous. In Delacroix’s artwork the linearity most of the time is achieved through color contrast. The painting’s chromatic drama corresponds with the rules of Romantic schema for the construction of psychological poetic depth within the painterly space. The artist is using light in order to create a dramatic three-dimensional volume.[24] For the purpose of Wolfflin’s theory of formalism, particularly referring to linear and painterly development, it will be helpful to compare two artworks of artists living and working at the same period of time, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres[25] and Eugène Delacroix. Ingres represented Neoclassic[26] and Delacroix the Romantic[27] Movement. For the sake of formal inquiry two samples of their artworks will be reviewed. The first is a fragment of Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (see fig.2) and the second Ingres’s Princess de Broglie (see fig.3). A comparison of the draperies and the parts of the bodies reveals two different personalities. In Delacroix’s fragment the strokes of the brush and layered color variations compose the impression of the flesh. In Ingres’ artwork the flesh is depicted with the great rigor of academic values; the various shadow tones construct an almost photographic depiction of reality. On the Ingres’ painting[28] it is impossible to distinguish the brush strokes, even under the magnifying glass. In contrast to Ingres’ artwork, the Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People roughly executed drapery confronts the sublime gradation of the Princess de Broglie’s crinolines. These are depictions of opposite worlds: the popular ordinary and the aristocratic, the revolutionary and the despotic, and finally the beautiful and the ugly.[29] It is also the reflection of two different feminine realities: one is the rough physical existence of the populist revolutionary and another is the one of the refined nobility. Delacroix expresses by the movements of his harsh brushstrokes the rebellious character of Romantic modernity. Ingres by the flatness of his static canvases and controlled perfection of his draughtsmanship exteriorizes the inflexibility and archaism of the academy system and its values. Delacroix’s roughly painted surface gives an impression of living entities. Ingres’ perfection emanates from the canvas’s surface with the severe unity of immobilized linearity of dead particles on it. The plasticity of the various elements of Delacroix’s painting and his virtuosity to play with the color and the line conclude the formal aesthetic unity of the whole picture. In general, the energy and the anxiety of chromatic life emanates from Delacroix’s artwork. Delacroix’s painterly and compositional formality serves perfectly to express the revolutionary ambiance and spiritual spontaneity and greatness of these historic moments. Delacroix aligned the materiality of the surface of his canvas to the subject of his concerns. Delacroix, through his style of painting reflects the demographic composite of the French society at his time. The Liberty Leading the People is an artwork documenting through its formality and visual symbolism a moment in the social history of the French nation.

This brings my attention to Arnold Hauser’s discussion of the Social History of Art. According to Hauser each art object is related to the socio-political and historical conditions in which it was created. Art plays a significant role in social history and is bounded to it by the moment of time it was executed. The artist’s perception of historical truth is regulated through general social conditions and it is necessary to take into consideration the circumstances leading to the creation of art, including its reception by the public. Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People confirms Hauser’s theory in terms of how socio-political conditions influence artistic creativity. In Delacoix’s image the historical fact of the July conflict is not represented literally but through the artist’s interpretation of it. Taking into consideration the socio-political situation in France just before the revolution, especially in Paris, the symbolic representation of its citizens in Delacroix’s vision refers to the social discontent of Parisians. The despotic methods of Charles X and his ministers aggravated significantly the already difficult situation among the poorest citizens of the overpopulated city. Delacroix approached the aspect of “Liberty” through the Romantic movement of its euphoric perception. The various elements of the painting reviewed from the historic point of view do not represent an “archival document” but its allegoric content reflects the revolutionary enthusiasm of Parisians at that time. Delacroix depicts the idealistic unity of various social classes and presents a psychological portrait of the revolution. Each character represented is representative of a specific social problem. The lack of unity and hesitation of bourgeoisie’ position is illustrated by the man with the top hat. He gives an impression of moving but the position of the rifle in his hands suggests uncertainty. The young boy with the pistols in his hands reflects the opposite attitude of young radicals bored with the insufficiency of changing governments. Also his image refers to the existing problems of young, poor, and homeless members of the society. On the left side of the painting the man with the sabre design, typical of the equipment of the Napoleonic cavalry, represents the aspirations of the working classes, ready to reconstitute republican values. The strongest emphasis is given to the representation of the women importance in the ideal functioning of the nation. The woman as an allegorical “Liberty” represents the principal structure of social health to any nation. The woman’s healthy naked torso and her basic dress refer to the “popular” identity as the nation real roots.

These few samples show how the social conditions surrounding the artists shaped his vision of reality. Delacroix’s representation of “Liberty” reflects also his rebellious attitude to the orthodoxy of Academy establishment. He imposed his artistic individuality of his revolutionary style of painting in every sense of this word. In the context of Delacroix’s fragile personality and his concerns about his artistic future at a time of social uncertainty his intelligence dictated him the necessity to depict the current of change.

[1] “Britannia” in England, “Kathleen Ni Houlihan” in Ireland, “Finnish maiden” in Finland, “Germania” in Germany, “Bharat Mata” in India, “Lady of the mountain” in Iceland, “ Srulik” in Israel, “Italia Turrita” in Italy, “Ola Nordmann” in Norway, “Polonia” in Poland, “Mother Russia” in Russia, “Mother Svea” in Sweden, “Helvetia” in Switzerland, “Liberty” in United States, and “Marianne” in France.

[2] Mary Wiseman in her article “Gendered Symbols” looks at Delacroix’s representation of “Liberty” in the context of men’s objectification of the women related to sexual desires.

[3] To mention just few: Benjamin Walter (1892-1940) German critic and philosopher. Edward Wadie Saïd (1935-2003), Palestinian American literary theorist, and cultural critic. Georges Bataille (1897-1962), French writer. Jacques Derrida (1930), French philosopher and theorist. Jacques Lacan (1901-1981), French psychoanalyst. Julia Kristeva (1941), Bulgarian-born French theorist and psychoanalyst. Frantz Fanon (1925-1961), psychiatrist and revolutionary critic from Martinique. Michel Foucault (1926-1984,) French philosopher and historian. Roland Barthes (1915-1980), French literary critic and theorist. Theodor Adorno (1903-1969), German philosopher and art critic.

[4] Arnold Hauser (1892-1978), English, Hungarian-born art historian, author of the book The Social History of Art, 1989.

[5] Peter Pauvel Rubens (1577-1640), the Flemish painter. He was Delacroix’s favourite artist. He named him the Homer of the painting. Romantic period in general nourished itself from the Baroque styles expressive imagery.

Damisch, Hubert, and Richard Miller. Reading Delacroix’s “Journal.” October, Vol. 15, (Winter, 1980): 16-39.

Delacroix, Eugene. Journal 1822-1863. Paris: Editions Plon, 1996.

[6] These particular models of rifles were fabricated around the 1816.

Jobert, Barthélémy. Delacroix. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1997.

Sérullaz, Arlette, and Vincent Pomarède. Eugene Delacroix La Liberte Guidant le Peuple. Paris: Musée du Louvre, Collection “Solo,” 2004.

[7] “July Revolution” of 1830 started the beginning of “July Monarchy” (1830-1848). Louis-Philippe de Orleans replaced the despotic king Charles X.

[9] The Romanticism followed the Neoclassic tendencies of the large canvases reserved to the heroic historical paintings as the highest form of art in the academic hierarchy.

[11] In September 1792, it was decided by the National Convention that the new seal of the state would represent a standing woman holding a spear and wearing the Phrygian cap.

Agulhon, M. Marianne into Battle: Republican imagery and symbolism in France. London: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

[12] The Marianne character first appeared during the French revolution of 1789. She represents the heroism of women and the French nation during the revolutionary struggles.

Agulhon, M. Marianne into Battle: Republican imagery and symbolism in France. London: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

Bélly, Lucien. Hisoire de France. Paris: Editions Gisserot, 1997.

[13] Various interpretations of this story exist in different publications. In this paper, the version described is taken from the Barthélémy Jobert’s book Delacroix from 1997); 132. The newspapers propagated the sad and patriotic gesture right after the July events.

[14] Marie Deschamps who was one who received the order from the state as an official recognition for her bravery.

Sérullaz, Arlette, and Vincent Pomarède. Eugene Delacroix La Liberte Guidant le Peuple. Paris: Musée du Louvre, Collection “Solo,” 2004.

Jobert, Barthélémy. Delacroix. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1997.

[15] The symbolic meaning of the yellow color varies from one culture to another and it is not always positive. To read the symbolic meaning in proper manner it is necessary to refer to the logical context of the image as a whole.

[16] Twenty years later in 1862, Victor Hugo inspired by Delacroix’s painting, created a literary character Gavroche in his famous novel Les Misérables.

[17] According to some scholars Delacroix portrayed himself as the noblemen in order to indicate his political position and declare his support to the revolutionary ideas. Most scholars agree that it was the case. The facial features correspond with Delacroix’s; the only problem is that he was quiet and conservative, as a person and he did not like any drastic changes, especially socio-political. Another scholars suggest that it might be Frédéric Villot, Félix Guillemarder, or Étienne Argo.

[18] The facial features of this character are either female or male. It is another symbolic reference to the French nation as a whole.

[19] Charles X (1757–1836) King of France and Navarre. His rules cause the revolutionary uprising in July of 1830. He was replaced by Louis-Philippe d’Orléans.

Bélly, Lucien. Hisoire de France. Paris: Editions Gisserot, 1997.

Sérullaz, Arlette, and Vincent Pomarède. Eugene Delacroix La Liberte Guidant le Peuple. Paris: Musée du Louvre, Collection “Solo,” 2004.

Pinkney, David H. “A New Look at the French Revolution of 1830.” The Review of Politics, Vol. 23, No. 4 (Oct., 1961): 490-506.

[21]Fragments of letters written by people who met Delacroix on the street during the July revolution such as: Alexandre Dumas, Charles Lenormant, Pierre Godiberte, Henrie Heine, and Teophile Thore.

Sérullaz, Arlette, and Vincent Pomarède. Eugene Delacroix La Liberte Guidant le Peuple. Paris: Musée du Louvre, Collection “Solo,” 2004.

Jobert, Barthélémy. Delacroix. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1997.

[22]The Massacre at Chios (1824), Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi (1826), The Death of Sardanapalus (1827).

[23] Delacroix elaborates on many occasions in his journal how important it is to compose painting with freedom of the brush and color in order to be able to create the impression of movement. Delacroix promoted the painterly chromatic school and Ingres promoted the opposite linear school. Their rivalry lasted until Delacroix’s dead.

Delacroix, Eugene. Journal 1822-1863. Paris: Editions Plon, 1996.

Sérullaz, Arlette, and Vincent Pomarède. Eugene Delacroix La Liberte Guidant le Peuple. Paris: Musée du Louvre, Collection “Solo,” 2004.

[24] The technique of using light to build the dramatic ambiance with sophisticated sensibility was mastered by Théodore Géricault (1781-1824), Delacroix’s close friend from in the studio of Pierre-Narcisse Guerin (1774-1833). It is evident that Delacroix appropriated this technique in his painting the Liberty Leading the People.

[25] Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), French painter and the leading representative of Neoclassicism. He was a ferocious rival of Delacroix’s modernity and freedom in painting style. Ingres represented a highly conservative academic approach to the art of painting. He considered drawing abilities as essential in art practices. He used to say that who can draw he can paint too.

Brookner, Anita. “Ingres.” Soundings. London: The Harvill Press, 1997.

Elbert, Hans. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Berlin: Henschelverlag Kunst und Gesellschaft, 1982.

[26] Movement in art starting at the end of 18ths century, and lasted to the beginning of 18th century. Neoclassicism is reappearing often in the various periods of the 20th century.

[27] Movement in art starting at the beginning of 18th century and lasted to the middle of 19th century.

[28] I always look and study every painting from very close range, as close as I can get to them. I have seen many times Ingres’ artwork and Delacroix’s too, during my regular trips to European museums.

[29] Delacroix was considered for a while as an “Apostle of Ugliness” by the conservative media (E.J. Delécluze) and some members of the academy. Coubert and Manet shared this epithet for the same reason as Delacroix did, for introduction of modernity in painting.

Sérullaz, Arlette, and Vincent Pomarède. Eugene Delacroix La Liberte Guidant le Peuple. Paris: Musée du Louvre, Collection “Solo,” 2004.

Jobert, Barthélémy. Delacroix. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1997.

Bibliography

Bélly, Lucien. Hisoire de France. Paris: Editions Gisserot, 1997.

Brookner, Anita. “Art Historians and Art Critics – VII: Charles Baudelaire.” The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 106, No. 735, French Nineteenth-Century Painting and Sculpture (Jun., 1964): 269-279.

Brookner, Anita. “Ingres.” Soundings. London: The Harvill Press, 1997.

Brookner, Anita. “Delacroix.” Soundings. London: The Harvill Press, 1997.

Brown, Roy Howard. “The Formation of Delacroix’s Hero between 1822 and 1831.” The Art Bulletin, Vol. 66, No. 2 (Jun., 1984): 237-254.

Damisch, Hubert, and Richard Miller. Reading Delacroix’s “Journal.” October, Vol. 15, (Winter, 1980): 16-39.

Delacroix, Eugene. Journal 1822-1863. Paris: Editions Plon, 1996.

Elbert, Hans. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Berlin: Henschelverlag Kunst und Gesellschaft, 1982.

Gauthier, Maximilien. Delacroix. Les Plus Grands Paintres Collection. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1963.

Georgel, Pierre, and Luigina Rossi Bortolatto. Tout l’Oeuvre Paint de Delacroix. Paris: Éditions Flammarion, 1975.

Gouma-Peterson, Thalia, and Patricia Mathews. “The Feminist Critique of Art History.” The Art Bulletin, Vol. 69, No. 3 (Sep., 1987): 326-357.

Grew, Raymond. “Picturing the People: Images of the Lower Orders in Nineteenth- Century French Art.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History, XVII:I Summer 1986:c 203-231.

Hauser, Arnold. Rococo, Classicism, and Romanticism. 1962. London: Routledge, 1989. Vol. 3 of The Social History of Art. 4 vol.

Hobsbawm, Eric. “Man and Woman in Socialist Iconography.” History Workshop, No. 6 (Autumn, 1978): 121-138.

Jobert, Barthélémy. Delacroix. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1997.

Kopalinski, Wladyslaw. Slownik Symboli. Warszawa: Wiedza Powszechna, 1990.

Lankford, E. Louis. “A Phenomenological Methodology for Art Criticism.” Studies in Art Education, Vol. 25, No. 3 (Spring, 1984): 151-158.

Lima, Marcelo Guimaraes. From Aesthetics to Psychology: Notes on Vygotsky’s “Psychology of Art.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 4, Vygotsky’s Cultural-Historical Theory of Human Development: An International Perspective (Dec., 1995): 410-424.

Mainardi, Patricia. “The Political Origins of Modernism.” Art Journal, Vol. 45, No. 1, Manet (Spring, 1985): 11-17.

Panofsky, Erwin. Meaning in Visual Arts. 1955. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, Phoenix edition, 1982.

Pinkney, David H. “A New Look at the French Revolution of 1830.” The Review of Politics, Vol. 23, No. 4 (Oct., 1961): 490-506.

Sérullaz, Arlette, and Vincent Pomarède. Eugene Delacroix La Liberte Guidant le Peuple. Paris: Musée du Louvre, Collection “Solo,” 2004.

Tormey, Judith Farr, and Alan Tormey. “Art and Ambiguity.” Leonardo, Vol. 16, No. 3, Special Issue: Psychology and the Arts (Summer, 1983): 183-187.

Wiseman, Mary. “Gendered Symbols.” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Summer, 1998): 241-249.